Christmas Carols

Christmas Carols - The Penguin Book

SING CHOIRS OF ANGELS.

by Ian Bradley

Ian Bradley reflects on the origins and development of Christmas carols.

The sound of of them, whether emanating from a supermarket sound system or from the lips of youthful wassailers going from house to house, is one of the surest signals that Christmas is coming. Yet although it now seems almost unthinkable to celebrate (or survive) the festive season without them, they originally had nothing to do with Christmas, nor even with Christianity.

Christmas Carols

They were among the many pagan customs taken over by the medieval church which used them initially as much in the celebration of Easter as of Christmas.

The subsequent development of the carol as a distinctive genre standing somewhere between the hymn; the folksong and the sacred ballad and having as its subject matter the story and significance of Jesus's birth serves as an interesting pointer to several major currents in British religions, social and cultural history over the last five hundred years.

Born out of late medieval humanism, they were suppressed by Puritan zealots after the Reformation, partially reinstated at the Restoration, sung by Dissenters and radicals to the distaste of the Established Church in the eighteenth century, rediscovered and reinvented by Victorian antiquarians and romantics, and re-written in the late twentieth century to fit the demand for social realism and political correctness.

As well as reflecting the mood of their times, some of our best loved examples also contain coded comments on contemporary events, including, perhaps, the 1745 Jacobite rebellion and the revolutions across Europe in 1848.

The derivation of the word `carol' has been the subject of much speculation. It probably goes back through the old French `caroler' and the Latin `choraula' to the Greek `choros', a circling dance often accompanied by singing and associated with dramatic performances, religious festivities and fertility rites.

The song of classical times was a major element in popular celebrations to mark the passing of the winter solstice and the promise of spring.

The coming of Christianity may well have increased the pagan connotations with its lively dance rhythms providing a marked contrast to the restrained and measured chants of the new religion.

The Church was for long uneasy about the performance of such popular singing-dances and the `caraula' was explicitly proscribed in a decree of the mid-seventh-century Council of Chalonsur-Saone.

The singing of them was further condemned by the Council of Avignon in 1209 and as late as 1435 by the Council of Basle. The earliest known reference to it in English literature, which dates from around 1300 and uses the word in its modern spelling, has no religious connotations and seems to denote simply a round dance.

Although the Church came relatively early to see the advantages of incorporating elements of pagan customs such as the Roman Saturnalia and the Germano-Celtic Yule in its celebration of Christ's nativity, it took much longer to be persuaded of the merits of such singing.

It was not until the austerity of early medieval Christianity had been tempered by the new spirit of imagination and romance associated with the twelfth-century renaissance that they were taken up as Christian folksongs.

Christmas Carols

The new humanism also brought a change of emphasis away from death and judgement towards a more incarnational focus on the humanity and personality of Jesus, in which the cradle became almost as important an object of devotion as the Cross.

Christmas Carols are not just for antiquarians and scholars, however. They belong to a living tradition which is constantly being added to with new material.

The last three decades have seen modern expressions of the Christmas story in Michael Perry's `Calypso Carol', Sydney Carter's `Every Star Shall Sing' with its references to space travel and John Bell's `Funny kind of night' which speaks of `Tax collectors, child inspectors, all in disarray'.

A song written in 1992 by Michael Forster, a Baptist minister, portrays Mary as a `blessed teenage mother'. Whatever feelings these and other modern lyrics stir up among traditionalists, there is no doubt that they conform to Percy Dearmer's oft-quoted definition of carols as

... songs with a religious impulse that are simple, hilarious, popular and modern ... set in such language as shall express the manner in which the ordinary man at his best understands the ideas of his age.

With the arrival of the politically correct, multi-faith carol, purged of any reference to men, Christ, cribs or angels, we have come back where we started -- with carols disconnected from Christmas or Christianity.

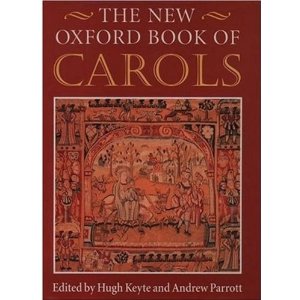

The New Oxford Book of Carols

Edited by early music experts Hugh Keyte and Andrew Parrott, this anthology of Christmas carols is the most comprehensive collection ever made, spanning seven centuries of caroling in Britain, continental Europe, and North America.

Christmas Carols

Containing music and text of 201 carols, many in more than one setting, the book is organized in two sections: composed carols, ranging from medieval Gregorian chants to modern compositions, and folk carols, including not only traditional Anglo-American songs but Irish, Welsh, German, Czech, Polish, French, Basque, Catalan, Sicilian, and West Indian songs as well.

Each carol is set in four-part harmony, with lyrics in both the original language and English. Accompanying each song are detailed scholarly notes on the history of the carol and on performance of the setting presented. The introduction to the volume offers a general history of carols and caroling, and appendices provide scholarly essays on such topics as fifteenth-century pronunciation, English country and United States primitive traditions, and the revival of the English folk carol.

The Oxford Book of Carols, published in 1928, is still one of Oxford's best-loved books among scholars, church choristers, and the vast number of people who enjoy singing carols.

This volume of Christmas Carols is not intended to replace this classic but to supplement it. Reflecting significant developments in musicology over the past sixty years, it embodies a radical reappraisal of the repertory and a fresh approach to it.

The wealth of information it contains will make it essential for musicologists and other scholars, while the beauty of the carols themselves will enchant general readers and amateur songsters alike.

Christmas Carols