|

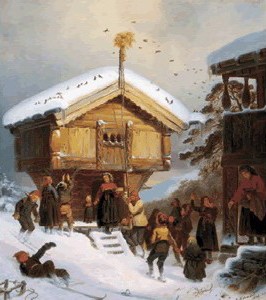

Christmas Eve Ancient CustomsChristmas in the narrowest sense must be reckoned as beginning on the evening of December 24. Throughout Europe its importance so far as popular customs are concerned is far greater than that of the Day itself, and nowhere is Christmas Eve more important than in Scandinavia. Then in Germany the Christmas tree is manifested in its glory; then, as in the England of the past, the Yule log is solemnly lighted in many lands; then often the most distinctive Christmas meal takes place. We shall consider these and other institutions later; though they appear first on Christmas Eve. Let us look first at the supernatural visitors, mimed by human beings, who delight the minds of children, on the evening of December 24, and at the beliefs that hang around this most solemn night of the year.

First of all, the activities of St. Nicholas are not confined to his own festival; he often appears on Christmas Eve. Of course, in Scandinavia he is the “nisse” or in Sweden “tomten”. In other countries he comes now vested as a bishop, now as a masked and shaggy figure. The names and attributes of the Christmas and Advent visitors are rather confused, but on the whole it may be said that in Protestant north Germany the episcopal St. Nicholas and his Eve have been replaced by Christmas Eve and the Christ Child, while the name Klas has become attached to various unsaintly forms appearing at or shortly before Christmas. We can trace a deliberate substitution of the Christ Child for St. Nicholas as the bringer of gifts. In the early seventeenth century a Protestant pastor is found complaining that parents put presents in their children's beds and tell them that St. Nicholas has brought them. No time in all the Twelve Nights and Days is so charged with the supernatural as the Eve before Christmas. It was to the shepherds keeping watch over their flocks by night that, according to the Third Evangelist, came the angelic message of the Birth, and in harmony with this is the unique Midnight Mass of the Roman Church, lending a peculiar sanctity to the hour of its celebration. And yet many of the beliefs associated with this night show a large admixture of paganism. First, there is the idea that at midnight on Christmas Eve animals have the power of speech. This superstition exists in various parts of Europe, and no one can hear the beasts talk with impunity. The idea has given rise to some curious and rather grim tales. In the Scandinavian countries simple folk have a vivid sense of the nearness of the supernatural on Christmas Eve. On Yule night no one should go out, for he may meet uncanny beings of all kinds. The Trolls are believed to celebrate Christmas Eve with dancing and revelry. “On the heaths witches and little Trolls ride, one on a wolf, another on a broom or a shovel, to their assemblies, where they dance under their stones.... In the mount are then to be heard mirth and music, dancing and drinking. On Christmas morn, during the time between cock-crowing and daybreak, it is highly dangerous to be abroad.”

Christmas Eve is also in Scandinavian folk-belief the time when the dead revisit their old homes, as on All Souls’ Eve in Roman Catholic lands. The living prepare for their coming with mingled dread and desire to make them welcome. When the Christmas Eve festivities are over, and everyone has gone to rest, the parlor is left tidy and adorned, with a great fire burning, candles lighted, the table covered with a festive cloth and plentifully spread with food, and a jug of Yule ale ready. Sometimes before going to bed people wipe the chairs with a clean white towel; in the morning they are wiped again, and, if earth is found, some kinsman, fresh from the grave, has sat there. Consideration for the dead even leads people to prepare a warm bath in the belief that, like living folks, the kinsmen will want a wash before their festal meal. Or again beds were made ready for them while the living slept on straw. Not always is it consciously the dead for whom these preparations are made, sometimes they are said to be for the Trolls and sometimes even for the Saviour and His angels. It is difficult to say how far the other supernatural beings—their name is legion—who in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland are believed to come out of their underground hiding-places during the long dark Christmas nights, were originally ghosts of the dead. Elves, trolls, dwarfs, witches, and other uncanny folk—the beliefs about their Christmas doings are too many to be treated here; readers of Danish will find a long and very interesting chapter on this subject in Dr. Feilberg's “Jul.” I may mention just one familiar figure of the Scandinavian Yule, Tomte Gubbe, a sort of genius of the house corresponding very much to the “drudging goblin” of Milton's “L'Allegro,” for whom the cream-bowl must be duly set. He may perhaps be the spirit of the founder guarding the family farm. At all events on Christmas Eve Yule porridge and new milk are set out for him, sometimes with other things, such as a suit of small clothes, spirits, or even tobacco. Thus must his goodwill be won for the coming year. In one part of Norway it used to be believed that on Christmas Eve, at rare intervals, the old Norse gods made war on Christians, coming down from the mountains with great blasts of wind and wild shouts, and carrying off any human being who might be about. In one place the memory of such a visitation was preserved in the nineteenth century. The people were preparing for their festivities, when suddenly from the mountains came the warning sounds. “In a second the air became black, peals of thunder echoed among the hills, lightning danced about the buildings, and the inhabitants in the darkened rooms heard the clatter of hoofs and the weird shrieks of the hosts of the gods.” The Scandinavian countries, Protestant though they were, retained many of the outward forms of Catholicism, and the sign of the cross was often used as a protection against uncanny visitors. In ancient times the cross—perhaps the symbol was originally Thor's hammer—is marked with chalk or tar or fire upon doors and gates, is formed of straw or other material and put in stables and cow houses as protection.

Christmas Eve

|